I once described someone this way, Mehta wrote in 2001: √ Players cigarette hung from his lower lip and threatened to fall off at any moment. I knew the brand of his cigarette from his chance remark. His hearing was so acute, for instance, that he was said to be able to tell the make of a car by the song of its motor. The congenitally bellicose Mailer died in 2007 without having made good on that vow.īut there was no trick to the keen visuality of his writing, Mehta said, beyond minute reporting, plumbing the inner depths of memory and the adroit use of the four senses at his disposal. Norman Mailer was reported to have charged that Mehta was not completely blind, threatening to punch him in the face. To some critics, the pinpoint acuity of these descriptions seemed too good to be true. The fields become bright, first with the yellow of mustard flowers outlined by the feathery green of sugarcane, and later with maturing stands of wheat, barley and tobacco.

∺t the close of winter, Basant-Panchami a festival honoring the god of work arrives, and everyone celebrates it by wearing yellow clothes, flying yellow kites and eating yellow sweetmeats, he wrote in ∽addyji (1972), the first volume of his memoir. (In the line of duty, he traversed India, Britain and the United States, including the teeming streets of New York, nearly always alone, with neither dog nor cane.)

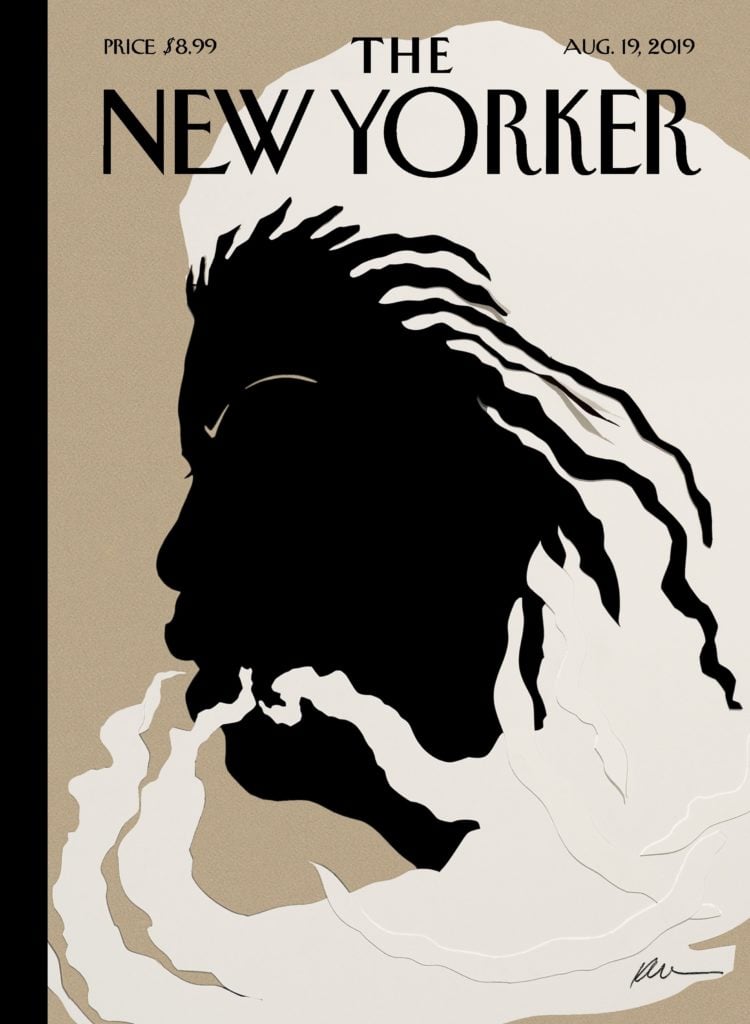

One of the most striking hallmarks of Mehtas prose was its profusion of visual description: of the rich and varied landscapes he encountered, of the people he interviewed, of the cities he visited. He could rework a single article more than a hundred times, he often said. His literary style derived partly from his singular way of working: Blind from the age of 3, Mehta composed all of his work orally, dictating long swaths to an assistant, who read them back again and again for him to polish until the work shone like a mirror. The recipient of a MacArthur Foundation genius grant in 1982, Mehta was long praised by critics for his forthright, luminous prose with its informal elegance, diamond clarity and hypnotic power, as The Sunday Herald of Glasgow put it in a 2005 profile. He writes about serious matters without solemnity, about scholarly matters without pedantry, about abstruse matters without obscurity. Ved Mehta has established himself as one of the magazines most imposing figures, The New Yorkers storied editor William Shawn, who hired him as a staff writer in 1961, told The New York Times in 1982. The cause was complications of Parkinsons disease, his wife, Linn Cary Mehta, said.Īssociated with the magazine for more than three decades much of his magnum opus began as articles in its pages Mehta was widely considered the 20th-century writer most responsible for introducing American readers to India.īesides his multivolume memoir, published in book form between 19, his more than two dozen books included volumes of reportage on India, among them Walking the Indian Streets (1960), Portrait of India (1970) and Mahatma Gandhi and His Apostles (1977), as well as explorations of philosophy, theology and linguistics. Ved Mehta, a longtime writer for The New Yorker whose best-known work, spanning a dozen volumes, explored the vast, turbulent history of modern India through the intimate lens of his own autobiography, died Saturday at his home in Manhattan.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)